Does a UK Chase Contestant's Self-Described Occupation Tell Us Anything More?

/In the previous blog post, I mentioned in passing that the new UK Chase data source I’d kindly been given included occupation, but said no more about it there.

That was largely because I knew that occupations were sufficiently diversely described that nothing meaningful was likely to be obtained by analysing using raw occupations alone - we’d have maybe thousands of unique occupations. What I knew I needed was some way of clustering those occupations, or grouping them based on some agreed schema.

One such schema is the Australia and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO), which is a 5-level schema, with some 1,746 unique occupations at its base level.

It turns out that the Australian Bureau of Statistics have recently launched a service that allows individuals and organisations to input an occupation along with up to three short descriptions of the occupation’s major tasks and, through an API, have the system return one or more likely standard occupations with an associated level of confidence. It’s called the Whole of Australian Government Occupation Coding Service (WoAGOCS) to which I applied for and obtained access.

After more than a week wrestling with httr, JSON, credentials, and the unforgiving syntax of query construction, I was finally able to start classifying the UK Chase contestant occupation data, one batch at a time.

As I ws running the 4,030 unique occupations in the Chaser contestant data through the service I was finding that about 1-in-8 records failed to be mapped to the ANZSCO schema at any level (the service attempts to map at the lowest standard occupation level, but will try to find something at higher levels if this fails) and so rooted around in the WoAGOCS documentation to discover that including a basic task list should improve the coding success rate. I didn’t have these for the Chaser contestant occupations and so, enter the AI tool, Claude.

Not All AI is Evil

I prompted Claude with the following:

“For each of the following job titles, create a list of the top two or three tasks associated with it. The task list should be short (no more than 75 characters in total) and separated by commas. Return the output in the form of a CSV”

It dutifully responded, and its results were impressive.

Here are three example responses:

Checkout Operator: Process transactions, handle cash, assist customers

Cheerleading Coach: Teach routines, train athletes, choreograph performances

Cheese Maker: Produce cheese, monitor aging, quality control

(Blessed, of course, are the cheese makers).

However, even with this additional information, WoAGOCS was still failing to classify over 11% of the 4,030 occupations.

Facing the task of either ignoring these contestants or manually finding another contestant occupation that seemed similar but that had been successfully coded, I had another couple of thoughts:

Realistically, I'm only going to be using for analytic purposes the top level of the ANZSCO schema, which comprises 8 levels

Managers

Professionals

Technicians and Trades Workers

Community and Personal Service Workers

Clerical and Administrative Workers

Sales Workers

Machinery Operators and Drivers

Labourers

Maybe Claude might be “smart” enough to directly classify jobs using these categories

I also recognised that there were quite a few student contestants in the UK Chase data, and so I added a ninth category to the list above and prompted Claude with:

“Categorise each of the job titles below into one of the following occupation classifications. Return the results as a CSV”

… after which I provided the 9-class schema described above.

Again, Claude performed admirably, even recognising that I was using the ANZSCO schema. As a base commonsense check on its output, I compared its results to those from WoAGOCS for those contestants where that system had returned a classification and found that there was about an 80% agreement.

The upside was that Claude provided a suggestion for all 4,030 occupations, so there was no need for any manual intervention from me. The downside was that, unlike WoAGOCS, Claude did not provide a confidence level alongside its suggestion, and provided only a single suggestion for each contestant.

I was unable to find any obvious hallucinations in Claude’s output and so, on balance, and in the interests of expediency and likely good-enough classifying, I went with the Claude suggestions.

(In passing, I’ll mention that Claude, of its own volition opted to classify “Unemployed” as “Student” because, as it put it:

“Special note: "Unemployed" was classified as "Student" as it typically represents a temporary status similar to being between studies or training periods in occupational classification systems.”

Also, it noted:

“Notable classification: "Dad" was categorized as Community and Personal Service Workers as it represents caregiving work in this occupational context.”

Claude also provided a considerable amount of other advisory notes explaining, for example, how it had differentiated amongst police roles, military roles, and IT roles.)

THE RESULTS

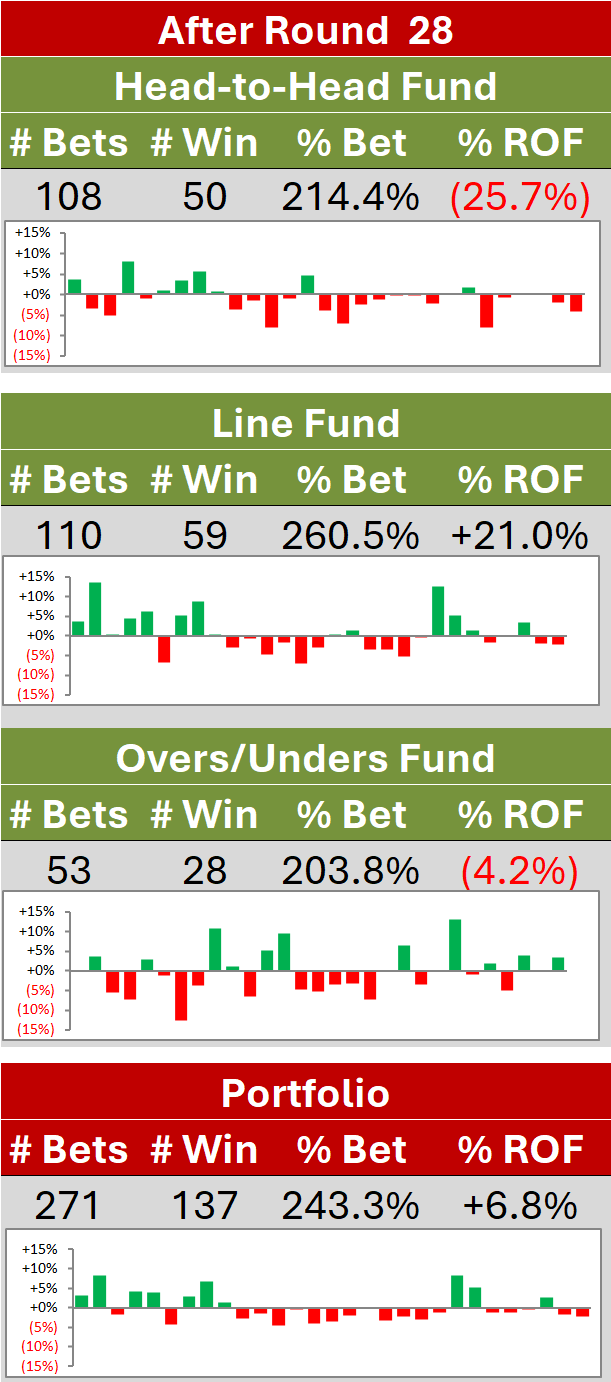

Counts, Means and Standard Deviations

Firstly, let’s look at the raw counts of UK Chase contestants that have an associated age, gender, and occupation in the data.

From the table at right we see that we have 8,784 such contestants whose average age is 43, who are split near 50:50 on gender, and who are predominantly classified by Claude as “Professional” (41%) or “Managers” (19%).

Next highest are Clerical aand Administrative Workers (12%) and then Community and Personal Service Workers (11%).

Just under 7% of the contestants are classified as “Students”

Only 1% are classified as Labourers, and 1.5% as Machinery Operators and Drivers.

Before continuing, it’s important for us to recognise that it is unlikely we have representative sample of contestants from any of the occupation groups (or of any age or gender cohorts), so all we can say about the results we get is that they apply to UK Chase contestants from each of these groups - which is the subset comprising those people who have the motivation to apply, the time to audition, and almost certainly the telegenicity to be selected by a producer or his or her staff.

Next, let’s put age and gender aside for a moment, since we analysed those two dimensions in the previous blog, and just focus on Cash Builder and Contributions to the Prize Fund by Occupation Group.

Here we can see, for example, that:

Contestants classified as Professionals have the highest average Cash Builder of £5,101

Next come Managers (£4,992), Labourers (£4,978), Technicians and Trade Workers (£4.967), and Machinery Operators and Drivers (£4,939)

Note the relatively large standard errors associated with the Cash Builder amounts for all occupation groups, signifying that occupation group is unlikely to be a very useful predictor of Cash Builder amounts

Contestants classified as Machinery Operators and Drivers have the highest average Contribution to the Prize Fund of £6,280. That’s because, as we can see in the table at right, they have a relatively high propensity to take the higher offer, and the second highest propensity to defeat the Chaser when they do choose this amount. (Also, on average, their High Offer is about 9.2 times their Cash Builder, which is similar to the ratio that other occupation groups enjoy)

Next highest in terms of average Contribution are Technicians and Trade Workers (£5,162), Professionals (£4,782), Managers (£4,767), and Community and Personal Service Workers(£4,447)

The even larger standard errors associated with the Contributed amounts for all occupation groups, signify that occupation group is unlikely to be a very useful predictor of Contributed amounts.

Predictive Models

Speaking of predicting Cash Builder and Contribution amounts, let’s bring back contestant age and gender and see how much more occupation group contributes.

In this first model we look to predict a contestant’s Cash Builder based on his or her gender, age, and occupation category. The model type is a Multivariate Adaptive Regression Spline, and it has a number of appealling features:

it will allow us to model the inverted U-shape relationship we found between age and Cash Builder amounts for both genders by using what are called hinges

it will be parsimonious about the variables that it allows into the final model by insisting that a variable’s inclusion improve the model’s R-squared by at least a minimum amount

it will allow us to include “interaction terms” (ie variables that are combinations of underlying variables) without inordinately risking overfitting.

The model that we get for predicting Cash Builder amounts is shown below.

As per the annotations, it shows that:

For a given age and occupation group, on average, males generate larger Cash Builders (by about 1/3 of a question)

Controlling for age and gender, contestants classed as Professionals on average generate Cash Builders about 1/6 of a question higher

There are inverted V-shaped relationships between age and average Cash Builder amounts that differ slightly by gender

The model finds no use for any occupation group other than Professional

The model only explains about 6% of the variability in Cash Builder amounts across contestants

Practically, what does that 6% mean in terms of the quality of the predictions we get from the model.

One other way to assess those predictions is to calculate how far away from the actual Cash Builder amounts they are. On this front we have:

Average absolute difference between actual and predicted Cash Builder: £1,475 (or about 1.5 correct questions)

Median absolute difference between actual and predicted Cash Builder: £1,247 (ie 50% of our errors will be larger and 50% smaller than this amount)

For our second and final model we’ll attempt to predict the amount that a contestant contributes to the final prize fund based on his or her Age, Gender, Cash Builder amount, and Occupation Group.

That model appears below.

As per the annotations, this model shows that:

For a given Cash Builder, age and occupation group, on average, males contribute more to the final prize fund (by about £1,400)

Controlling for age and gender, contestants with Cash Builders greater than £4,000 contribute about £950 for every additional question they get right in the Cash Builder.

There is an inverted V-shaped relationship between age and average Amount Contributed, the shape of which is independent of gender

The model finds no use for any occupation group

The model only explains about 4% of the variability in Amount Contributed across contestants

Looking at the errors from this model, we have:

Average absolute difference between actual and predicted Amount Contributed: £4,140

Median absolute difference between actual and predicted Cash Builder: £2,027

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

If we already have a contestant’s age and gender, adding his or her occupation group allows us to very slightly better predict his or her Cash Builder, but makes no meaningful difference to our ability to predict the amount he or she will ultimately contribute to the prize fund.

Also, the order of importance of contestant characteristics for predicting his or her Cash Builder amount is:

Age

Gender

Occupation Group

Finally, the order of importance of contestant characteristics for predicting his or her Amount Contributed is:

Cash Builder amount

Age

Gender