And May All Your Probabilities Be Well-Calibrated

/Say I believe that Melbourne are a 20% chance to win a hypothetical game of football - and some years it seems that this is the only type of game they have any chance of winning - yet you claim they're a 40% chance. How, and when, can we determine whose probability is closer to the truth?

In situations like this one where a subjective probability assessment is required people make their probability assessments using any information they have that they believe is relevant, weighting each piece of that knowledge according to the relative importance they place on it. So the difference between your and my estimates for our hypothetical Melbourne game could stem from differences in the information we each hold about the game, from differences in the relative weights we apply to each piece of information, or from both of these things.

If I know, for example, that Melbourne will have a key player missing this weekend and you don't know this - a situation known as an "information asymmetry" in the literature - then my 20% and your 40% rating might be perfectly logical, albeit that your assessment is based on less knowledge than mine. Alternatively, we might both know about the injured player but you feel that it has a much smaller effect on Melbourne's chances than I do.

So we can certainly explain why our probability assessments might logically be different from one another but this doesn't definitively address the topic of whose assessment is better.

In fact, in any but the most extreme cases of information asymmetry or the patently inappropriate weighting of information, there's no way to determine whose probability is closer to the truth before the game is played.

So, let's say we wait for the outcome of the game and Melbourne are thumped by 12 goals. I might then feel, with some justification, that my probability assessment was better than yours. But we can only learn so much about our relative probability assessment talents by witnessing the outcome of a single game much as you can't claim to be precognitive after correctly calling the toss of a single coin.

To more accurately assess someone's ability to make probability assessments we need to observe the outcomes of a sufficiently large series of events for each of which that person had provided a probability estimate beforehand. One aspect of the probability estimates that we could them measure is how "calibrated" they are.

A person's probability estimates are said to be well-calibrated if, on average and over the longer term, events to which they assign an x% probability occur about x% of the time. A variety of mathematical formulae (see for example) have been proposed to measure this notion.

For this blog I've used as the measure of calibration the average squared difference between the punter's probability estimates and the outcome, where the outcome is either a 1 (for a win for the team whose probability has been estimated) or a 0 (for a loss for that same team). So, for example, if the punter attached probabilities of 0.6 to each of 10 winning teams, the approximate calibration for those 10 games would be (10 x (1-0.6)^2)/10 = 0.16.

I chose this measure of calibration in preference to others because, empirically, it can be used to create models that explain more of the variability in punting returns. But, I'm getting ahead of myself - another figure of speech whose meaning evaporates under the scantest scrutiny.

The table below shows how calibration would be estimated for four different punters.

By way of contexting the calibration score, note that the closer a punter's score is to zero, the better calibrated are his or her probability assessments, and a punter with absolutely no idea, but who knows this and therefore assigns a probability of 0.5 to both team's chances in every game, will have a calibration score of 0.25 (see Punter #2 above). Over the period 2006 to 2009, the TAB Sportsbet bookmaker's probability assessments have a calibration score of about 0.20, so the numerically tiny journey from a calibration score of 0.25 to one of 0.20 traverses the landscape from the township of Wise Ignorance to the city of Wily Knowledge.

Does Calibration Matter?

It's generally desirable to be labelled with a characteristic that is prefixed with the word stem "well-", and "well-calibrated" is undoubtedly one such characteristic. But, is it of any practical significance?

In your standard pick-the-winners tipping competition, calibration is nice, but accuracy is king. Whether you think the team you tip is a 50.1% or a 99.9% chance doesn't matter. If you tip a team and they win you score one; if they lose, you score zero. No benefit accrues from certainty or from doubt.

Calibration is, however, extremely important for wagering success: the more calibrated a gambler's probability assessments, the better will be his or her return because the better will be his or her ability to identify market mispricings. To confirm this I ran hundreds of thousands of simulations in which I varied the level of calibration of the bookmaker and of the punter to see what effect it had on the punter's ROI if the punter followed a level-staking strategy, betting 1 unit on those games for which he or she felt there was a positive expectation to wagering.

(For those of you with a technical bent I started by generating the true probabilities for each of 1,000 games by drawing from a random Normal distribution with a mean of 0.55 and a standard deviation of 0.2, which produces a distribution of home-team and away-team probabilities similar to that implied by the bookie's prices over the period 2006 to 2009.

Bookie probabilities for each game were then generated by assuming that bookie probabilities are drawn from a random Normal with mean equal to the true probability and a standard deviation equal to some value - which fixed for the 1,000 games of a single replicate but which varies from replicate to replicate - chosen to be in the range 0 to 0.1. So, for example, a bookie with a precision of 5% for a given replicate will be within about 10% of the true probability for a game 95% of the time. This approach produces simulations with a range of calibration scores for the bookie from 0.187 to 0.24, which is roughly what we've empirically observed plus and minus about 0.02.

I reset any bookie probabilities that wound up above 0.9 to be 0.9, and any that were below 0.1 to be 0.1. Bookie prices were then determined as the inverse of the probability divided by one plus the vig, which was 6% for all games in all replicates.

The punter's probabilities are determined similarly to the bookie's except that the standard deviation of the Normal distribution is chosen randomly from the range 0 to 0.2. This produced simulated calibration scores for the punter in the range 0.188 to 0.268.

The punter only bets on games for which he or she believes there is a positive expectation.)

Here's a table showing the results.

So, reviewing firstly items from the top row we can say that a punter whose probability estimates are calibrated at 0.20 (ie as well-calibrated as the bookies have been over recent seasons) can expect an ROI of negative 22% if he or she faces a bookie whose probability estimates are calibrated at 0.19. Against a bookie whose estimates are instead calibrated at 0.20, the punter can expect to lose about 7%, or a smidge over the vig. A profit of 9% can be expected if the bookie is calibrated at 0.21.

The table on the right shows just how often the punter can expect to finish in the black - for the row we've been looking at about 2% of the time when facing a bookie calibrated at 0.19, and 89% of the time when facing a bookie calibrated at 0.21.

You can see in these tables how numerically small changes in bookie and punter calibration produce quite substantial changes in expected ROI outcomes.

Scanning the entirety of these tables makes for sobering reading. Against a typical bookie, who'll be calibrated at 0.2, even a well-calibrated punter will rarely make a profit. The situation improves if the punter can find a bookie calibrated at only 0.21, but even then the punter must themselves be calibrated at 0.22 or better before he or she can reasonably expect to make regular profits. Only when the bookie is truly awful does profit become relatively easy to extract, and awful bookies last about as long as a pyromaniac in a fireworks factory.

None of which, I'm guessing, qualifies as news to most punters.

One positive result in the table is that a profit can still sometimes be turned even if the punter is very slightly less well-calibrated than the bookie. I'm not yet sure why this is the case but suspect it has something to do with the fact that the bookie's vig saves the well-calibrated punter from wagering into harmful mispricings more often than it prevents the punter from capitalising on favourable mispricings,

Looking down the columns in the left-hand table provides the data that underscores the importance of calibration. Better calibrated punters (ie those with smaller calibration scores) fare better than punters with poorer calibration - albeit that, in most cases, this simply means that they lose money as a slower rate.

Becoming better calibrated takes time, but there's another way to boost average profitability for most levels of calibration. It's called Kelly betting.

Kelly Betting

The notion of Kelly betting has been around for a while. It's a formulaic way of determining your bet size given the prices on offer and your own probability assessments, and it ensures that you bet larger amounts the greater the disparity between your estimate of a team's chances and the chances implied by the price on offer.

When used in the simulations I ran earlier it produced the results shown in the following table:

If you compare these results with those shown earlier using level-stake wagering you find that Kelly betting is almost always superior, the exception being for those punters with poor calibration scores, that is, generally worse than about 0.24. Kelly betting, it seems, better capitalises on the available opportunities for those punters who are at least moderately well-calibrated.

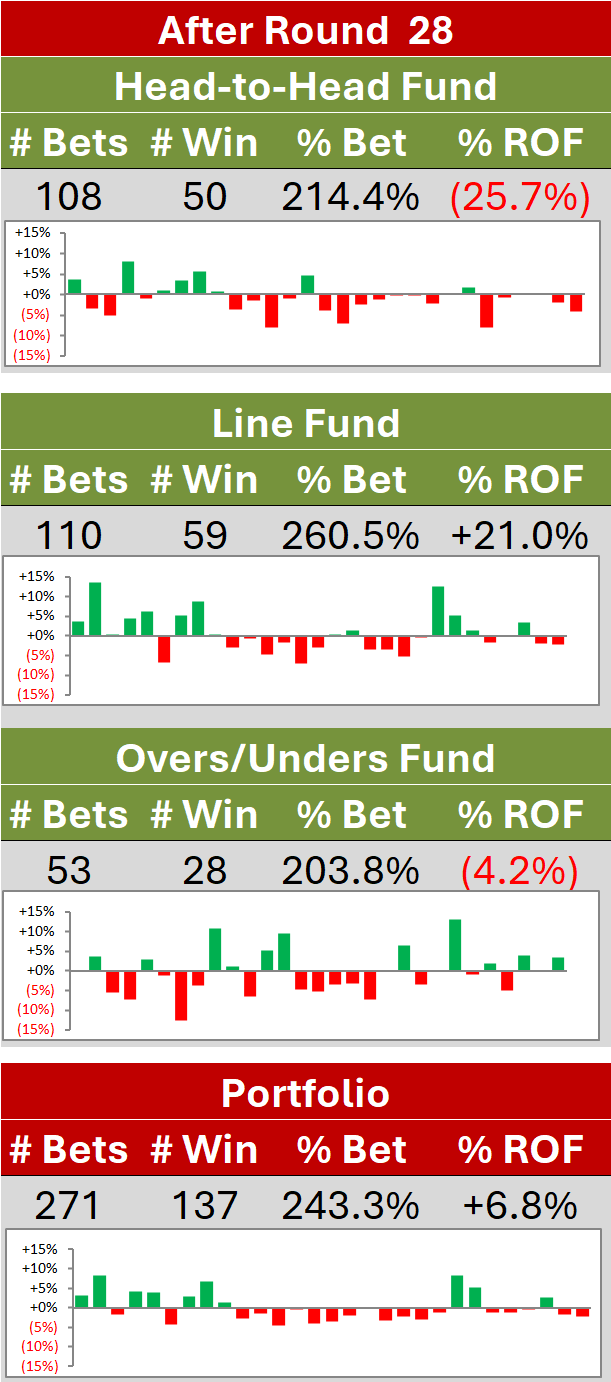

This year, three of the Fund algorithms will use Kelly betting - New Heritage, Prudence, and Hope - because I'm more confident that they're not poorly-calibrated. I'm less confident about the calibration of the three new Fund algorithms, so they'll all be level-staking this season.