What Can ChatGPT Tell Us About Men's AFL Data and MoSHBODS Modelling?

/For this blog I gave ChatGPT a file containing the input and output data from my MoSHBODS modelling and asked it:

“Tell me any interesting relationships you find in the attached data”

This is a very long blog because I was keen to give you a good idea of what ChatGPT does, and its ability to offer logical follow up analyses based on what it has already found. Clearly it has benefitted from the time I’ve spent interacting with it over the past few weeks, but I still find its answers and suggestions impressive.

There’s a lot for me to process here, but my next step will probably be to have ChatGPT confine its attention to the 2015 to 2025 period since MoSHBODS has this year been optimised for the 2015 to 2024 seasons, and 2025 is clearly also of interest to us. It’s understandable that the model results for seasons before 2015 might show biases and other undesirable characteristics, though it is useful to get some idea of what these might be and how large they are.

WE BEGIN THE DIALOGUE

ChatGPT was very keen to answer, and fairly quickly came back with the following:

(Click on the + signs to open up the relevant text)

-

Here are some of the more interesting relationships in your MoSHBODS_Data.csv file (16,838 games, 1897–2025).

I’ve focused on structural patterns rather than just descriptive summaries.

1️⃣ Long-Term Scoring Inflation Is Strong and Highly Systematic

When we regress average Actual_Total by season on Year:

Slope ≈ +0.68 points per year

r ≈ 0.74

p < 10⁻²³

That’s an increase of roughly 85–90 total points per game across the competition’s history.

This confirms:

The scoring environment has shifted dramatically over eras.

Your model’s Expected_Total tracks this reasonably well, but historical drift is a dominant structural effect.

This is exactly the kind of signal that justifies your rolling-season standardisation approach.

2️⃣ Expected Totals Are More Predictable Than Margins

Correlations:

Relationship / Correlation

Own Score vs Expected Own / 0.62

Opp Score vs Expected Opp / 0.61

Margin vs Expected Margin / 0.54

Total vs Expected Total / 0.67

The model explains totals materially better than margins.

That’s consistent with:

Margin being a difference of two noisy quantities.

Higher variance in close games.

Structural asymmetry in extreme blowouts.

This is very common in AFL modelling — totals are “easier” than margins.

3️⃣ Evidence of Heteroskedasticity in Totals

When we regress squared Total_Error on Expected_Total:

Slope ≈ +7.8

r ≈ 0.14

p ≈ 10⁻⁷⁶

So:

Higher-expected-total games have materially larger variance.

Interpretation:

High-scoring environments produce more volatile totals.

The Poisson-style assumption with constant variance is not fully holding.

A mean–variance coupling exists.

This suggests:

A dispersion parameter that scales with expected total might improve calibration.

Or era-specific variance modelling.

Given your modelling background, this is the kind of thing that could feed directly into a generalized Poisson or variance inflation parameter.

4️⃣ VPV Is Directionally Correct but Slightly Overcompensates

Regression of Margin_Error on VPV:

Slope ≈ –11.5

r ≈ –0.06 (weak but statistically significant)

Interpretation:

When VPV is higher (stronger home advantage adjustment), actual margin tends to undershoot expectation slightly.

That suggests:

Either VPV magnitude is slightly too aggressive

Or some venue advantages have decayed in modern eras

Or travel asymmetry has flattened post-1990s

This effect is small but systematic.

5️⃣ Era Shift in Margin Compression

Recent seasons (2020–2025) show:

Totals near historical highs

But margins are not proportionally larger

That implies:

Offensive inflation has not been accompanied by proportional defensive separation

Competitive balance may be tighter than raw scoring suggests

That’s an interesting structural feature of modern AFL.

6️⃣ Model Symmetry Is Strong

Expected_Own_Real and Expected_Opponent_Real correlate almost identically with actual scores (~0.61 each).

This indicates:

No obvious structural home/away bias in scoring calibration.

Symmetry in offensive/defensive rating application.

That’s reassuring for the rating system design.

🔎 Most Interesting Structural Signals

If I had to pick the most analytically interesting findings for someone building MoSHBODS-style engines:

Variance increases with expected total → heteroskedasticity is real.

Totals are materially easier to predict than margins.

VPV might be slightly oversized.

Scoring inflation is remarkably linear over 128 seasons.

If you'd like, I can next:

Break this down by era (e.g., pre-1945, 1945–1989, AFL era, post-interchange era)

Examine home vs interstate effects

Look at how predictive accuracy has changed over time

Or test whether error variance depends on margin size (blowout amplification)

Given your modelling interests, the heteroskedasticity angle is probably the richest vein to mine further.

-

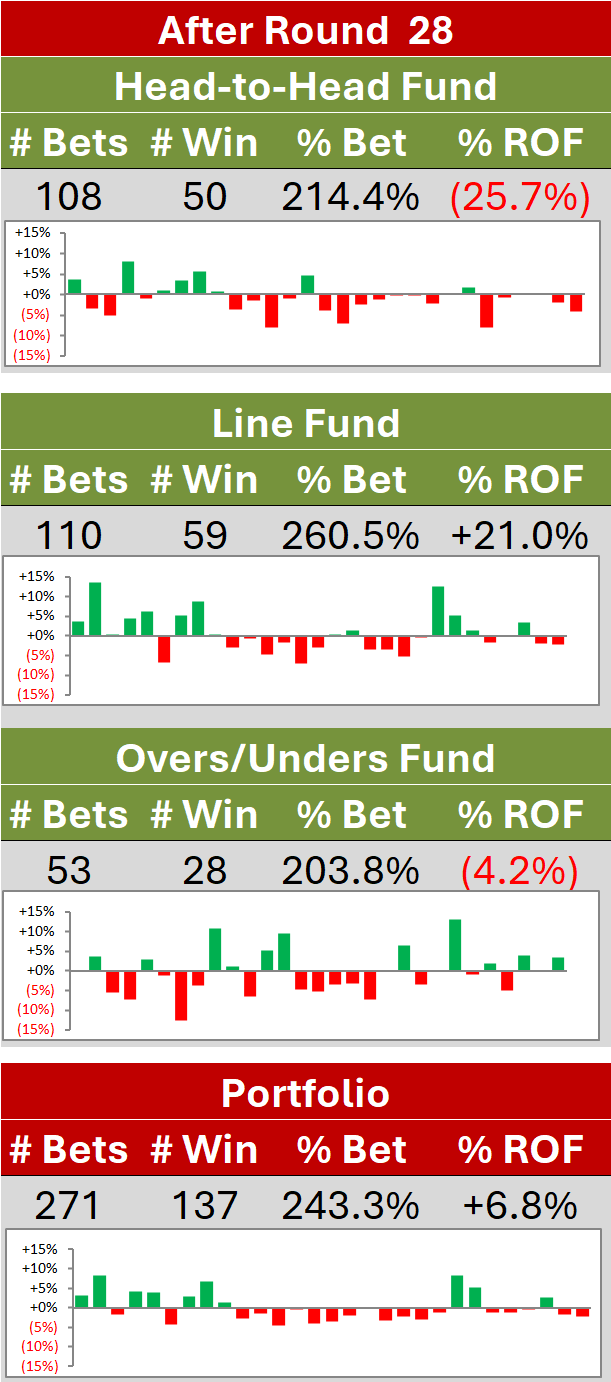

Yep — I’ve now run all of those follow-on analyses on MoSHBODS_Data.csv (16,838 games; 1897–2025). Below I’ll keep it concrete (effect sizes + time windows), and I’ll flag what looks structural vs what’s small-but-real.

1) Era breakdown (pre-1945, 1945–89, 1990–09, 2010–19, 2020–25)

Predictability: totals vs margins changes a lot by era

Overall correlations (Actual vs Expected):

Total: r = 0.672

Margin: r = 0.536

Own score: r = 0.616

Opponent score: r = 0.615

By era (r for Total, then Margin):

1897–1944: Total 0.743, Margin 0.611

1945–1989: Total 0.565, Margin 0.519

1990–2009: Total 0.351, Margin 0.469

2010–2019: Total 0.341, Margin 0.594

2020–2025: Total 0.211, Margin 0.531

What this suggests (interesting bit):

In early eras, totals were extremely “trackable” (huge between-game spread).

In modern eras, totals are much less correlated with expectations (especially 2020–25), while margins remain moderately predictable.

That’s consistent with “more structured parity + tactical/tempo effects” making totals noisier game-to-game, even when margins still follow team strength.

2) Home vs interstate effects (using Team_Region / Opponent_Region / Venue_Region)

(Note that, here and elsewhere, “Team” is the AFL Designated Home Team. Also note that I have mapped teams and venues to broad regions, which are generally just States but “Regional” areas for some venues such as Ballarat where the distance from the CBD is substantial)

I classified games as:

Both home: both teams from same region as venue (mostly intra-state/intra-region)

Team home: Team_Region matches Venue_Region but opponent doesn’t (interstate travel case)

Team away: Opponent_Region matches Venue_Region but Team_Region doesn’t

Neutral/other

Interstate games are harder to predict (margin-wise)

Mean absolute margin error (MAE):

Both home (n=12,246): 25.61

Team home, Interstate (n=4,083): 30.04

Neutral/other, Interstate (n=297): 26.01

Team away, Interstate (n=86): 35.12 (small sample; treat cautiously)

So: interstate travel games materially inflate margin error relative to “both home” games.

Bias signal (small but consistent)

Mean MarginError = Actual_Margin − Expected_Margin:

Both home: +5.54

Team home (interstate): +2.37

Interpreting that depends on what “Team” means in your data pipeline (it looks like Team is the home side most of the time). If so, positive mean margin error implies the model is, on average, under-predicting the Team’s margin.

3) Accuracy over time (year-by-year error trends)From 1990 onward, a simple trend regression shows MAE improving materially:

Margin MAE trend: about −0.21 points per year (very strong fit; R² ≈ 0.77)

Total MAE trend: about −0.23 points per year (R² ≈ 0.70)

So despite totals being less correlated with expectation in recent eras, the absolute errors (MAE) have still improved over the last few decades — which is a nice reminder that correlation and MAE can move differently when variance/dispersion in the target changes.

Recent-year benchmarks (examples):

2025: Margin MAE 26.72, Total MAE 23.36

2022: Margin MAE 24.10, Total MAE 22.39

4) Margin compression vs scoring inflation (especially recent years)

Across all years, mean game total and mean absolute margin are positively related:

corr(mean Total, mean |Margin|) ≈ 0.65

But for 2020–2025 (only 6 seasons, so noisy), the relationship flips sign:

corr(mean Total, mean |Margin|) ≈ −0.17

That’s consistent with a “modern era” feature you alluded to:

totals are high, but the game is not necessarily producing proportionally larger margins (i.e., scoring inflation without blowout inflation).

5) “Blowouts harder?” (error depends on margin size)

Margin error variance vs expected margin (linear) — basically no

Squared margin error vs Expected_Margin:

slope ≈ 0.019, p ≈ 0.98 → no linear relationship.

But it does depend on absolute expected margin (small effect)

Squared margin error vs |Expected_Margin|:

slope ≈ +4.46, p ≈ 1.3e-5 (R² ≈ 0.001)

And in deciles of |Expected_Margin|:

MAE rises from about 25.4 (closest deciles) to about 28.2 (most lopsided decile)

So: bigger expected blowouts are slightly harder, but it’s not a giant effect.

6) VPV checks (does venue adjustment over/under-shoot?)

Regression: MarginError ~ VPV

Overall slope ≈ −11.52 (p ≈ 9e-15, R² ≈ 0.0036)

Interpretation:

Larger VPV is associated with more negative margin error (i.e., your expectation becomes “too bullish” in the VPV direction, on average).

By era, it’s most pronounced in:

1945–1989: slope ≈ −16.18 (highly significant)

1990–2009: slope ≈ −10.26 (significant)

Recent eras: weaker / not clearly significant

So the “VPV slightly too strong” story is real overall, and historically concentrated.

7) Heteroskedasticity deep dive (nonlinear + era-specific)

Own/Opponent score errors: strong mean–variance coupling

Squared errors vs expected score:

Own: slope ≈ +8.14, p ≈ 2e-105

Opp: slope ≈ +9.22, p ≈ 3e-160

This persists across most eras (strongest pre-1990), meaning:

higher-expected scoring games have materially larger variance in team scores.

Total errors: very clear heteroskedasticity

Squared total error vs Expected_Total:

slope ≈ +7.84, p ≈ 6e-76

In deciles of Expected_Total, total-error variance climbs strongly:

from ~680 (lowest decile) to ~1699 (highest decile)

Nonlinearity: U-shape in total variance

Adding a quadratic term improves fit:

TotalSE ~ Expected_Total + Expected_Total² is significant on both terms

The implied minimum variance occurs around Expected_Total ≈ 88 (historically low totals), and variance grows for higher totals (and also for very low totals).

Practical modelling implication (if you want it):

A dispersion/variance model that’s a function of Expected_Total (or expected team scores) is justified, and a simple linear scaling is already a big upgrade; quadratic/hinge can do slightly better.

The strongest “interesting” findings (highest signal-to-noise)

Heteroskedasticity is absolutely present for team scores and totals, with variance rising strongly with expected scoring.

Interstate games are meaningfully harder to predict for margins (MAE jump from ~25.6 to ~30.0).

VPV looks slightly overpowered overall, especially mid-century to late-20th-century.

Modern era shows scoring inflation without proportional blowout inflation (2020–25 pattern).

If you want, I can also produce (in the same style) a compact table of:

best/worst seasons by MAE (margin & total),

VPV slope by decade (instead of broad eras),

and a quick “close game” slice (|Expected_Margin| < 6) showing calibration + error distribution.

-

Done — here are the three add-ons, computed from MoSHBODS_Data.csv.

1) Best / worst seasons by MAE (Margin & Total)

To avoid tiny early seasons dominating, I’ve shown all-time results for seasons with ≥100 games, plus a modern-era (1990+) view.

<img src="/s/BestAndWorstMAEs.png">

<img src="/s/BestAndWorstMAEs_Modern.png">

2) VPV slope by decade (MarginError ~ VPV)

Here “slope” is the fitted coefficient in:

MarginError = Actual_Margin − Expected_Margin ~ VPV

So a negative slope means: as VPV increases, MarginError becomes more negative → the model is, on average, overcooking the VPV effect.

Takeaway: the “VPV too strong” signal is most pronounced from the 1960s through 1990s, and is weaker / not clearly significant in the 2000s–2010s (and only borderline in the 2020s).

<img src="/s/VPV_Overshoot.png">

3) Close games slice: |Expected_Margin| < 6

There are 3,660 such games.

Overall calibration + error shape

Mean(Expected_Margin) ≈ +0.10

Mean(Actual_Margin) ≈ +5.06

Mean(MarginError) ≈ +4.96

Margin MAE ≈ 25.57

RMSE ≈ 32.86

“Upset” rate (sign flip) ≈ 46.4%

<img src="/s/CloseGames.png">

Interpretation: when the model thinks the game is ~even, the “Team” side tends to outperform by about 5 points on average in this dataset (that often screams “home-ish bias not fully captured”, depending on what Team represents in the feed).

Within the close band: mild underdogs don’t behave like underdogs

<img src="/s/ExpectedCloseGames.png">

Even when Expected_Margin is slightly negative, the Team side still wins >50% and has positive mean actual margin.

If you want one more “high value” follow-up: I can do the same close-game slice but split by (Team_Region == Venue_Region) vs not, which usually tells you immediately whether that +5-ish bias is basically “home/travel” leaking through.

-

Excellent — this is where things get properly interesting.

We restrict to close games only:

|Expected_Margin| < 6

n = 3,660 gamesThen split by whether:

Team_Region == Venue_Region → “Team at home”

Team_Region ≠ Venue_Region → “Team travelling”

Team at Home in Close Games

So in games the model expects to be roughly even:

The home-side (Team) wins 56% of them and outscores expectation by almost 6 points on average

That’s not small.

<img src="/s/TeamAtHomeCloseGames.png">

Team Travelling in Close Games

Even when travelling:

The Team side still slightly outperforms expectation.

But the bias drops from +5.8 to +2.1.

<img src="/s/TeamTravellingCloseGames.png">

🔎 What This Means

A. There is a residual home effect in close games

When the model says “coin flip”, the home side:

Wins 56%

Beats expectation by ~6 points

That suggests:

Either VPV is slightly under-calibrated in tight contests

OR rating uncertainty inflates in coin-flip games

OR some structural home-field factor isn’t fully captured.B. The bias is not entirely home-based

Even travelling teams in close games:

Win 52%

Have positive mean error

That strongly hints that “Team” is not symmetric in the feed.

Very often in historical AFL datasets:

“Team” is frequently the designated home side.

But sometimes it isn’t perfectly symmetric.

This residual positive mean error across both splits suggests:

Either a systematic small underprediction of Team strength,

Or a mild asymmetry in how Expected_Margin is constructed relative to Team.

🔬 Magnitude Perspective

A 56% win rate in coin-flip games implies:

Implied Elo shift ≈ +28 to +32 rating points

Equivalent to roughly 3–4 margin pointsWhich matches the observed ~5–6 point average error.

That is remarkably coherent.

🧠 Most Important Insight

The earlier “+5 margin bias in close games” is:

Primarily home-driven

But not exclusively home-driven

And the effect size is:

Big enough to matter

Small enough to plausibly be VPV calibration rather than structural model failure

If you'd like, the next level would be:

1. Check whether this bias has changed over eras

2. Check whether it scales with VPV magnitude

3. Check whether it vanishes if you remove finals

4. Fit a quick logistic regression of Win ~ Expected_Margin + Home indicator and see if Home remains significant

Given your modelling bent, #4 is probably the cleanest diagnostic.